When you’re over 65, the same pill that worked perfectly at 45 might make you dizzy, confused, or even sick. That’s not because the medicine changed - it’s because your body did. Aging affects how your body absorbs, distributes, metabolizes, and gets rid of drugs. What was once a safe dose can become dangerous. The key isn’t just taking less - it’s taking the right amount for your body right now.

Why Your Body Handles Medications Differently After 65

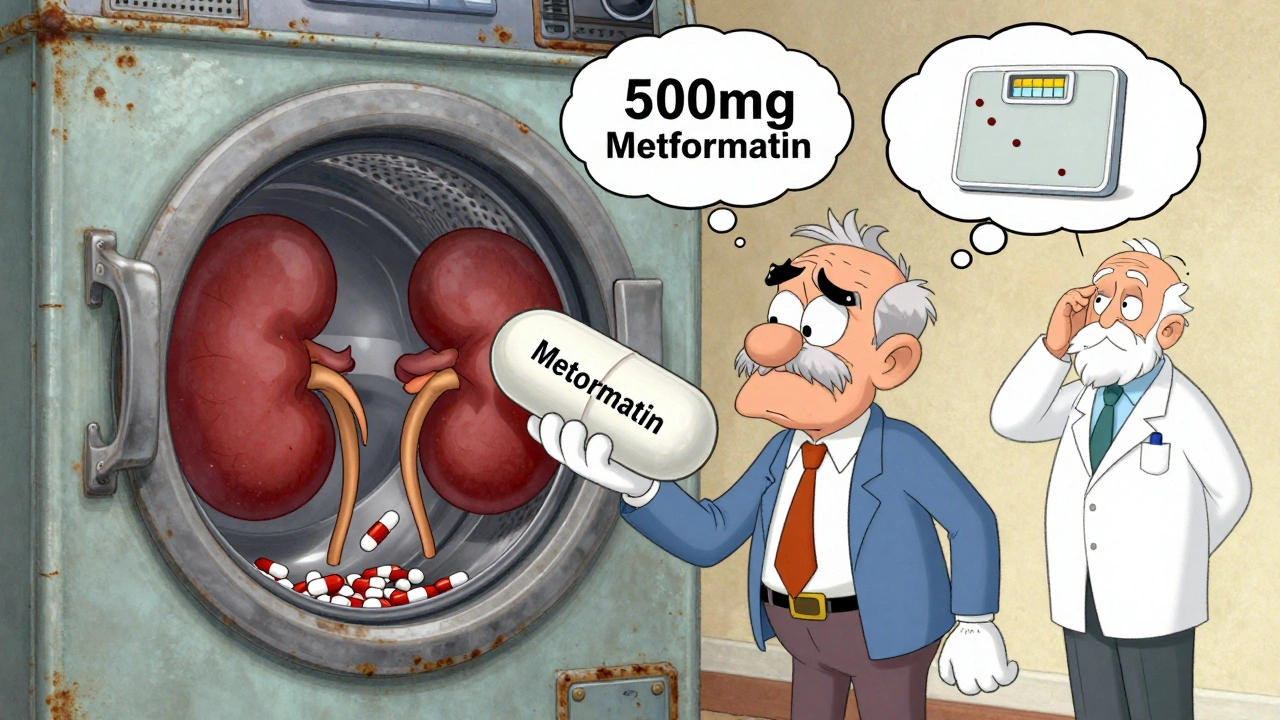

Your liver doesn’t process drugs like it used to. Your kidneys slow down. Your body composition shifts - you lose muscle, gain fat. These aren’t minor changes. They change how drugs move through you and how long they stay active.For example, drugs that are cleared by the kidneys - like gabapentin, metformin, or certain antibiotics - build up in your system if your kidney function drops. About 40% of adults over 65 have a glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) below 60 mL/min/1.73m². That’s not normal. It means your kidneys are working at less than half capacity. If you’re still taking the same dose you did at 50, you’re likely overdosing.

And it’s not just the kidneys. Your liver’s ability to break down drugs falls by 30-50% with age. That’s why medications like diazepam, warfarin, or statins can linger longer and cause side effects like drowsiness, bleeding, or muscle pain. Even your stomach changes - less acid means some pills don’t dissolve properly. Your body fat increases, so fat-soluble drugs like some antidepressants or benzodiazepines get stored longer, leading to prolonged effects.

The ‘Start Low, Go Slow’ Rule Isn’t Just Advice - It’s Science

The American Geriatrics Society has pushed the ‘start low, go slow’ principle since the 1980s. It’s not a suggestion. It’s a rule backed by decades of data. For most medications in older adults, the initial dose should be 25-50% lower than the standard adult dose.Take metformin. The usual starting dose for someone under 65 is 500 mg once or twice daily. For someone over 70 with even mild kidney decline, doctors should start at 250 mg and only increase if blood sugar stays high and kidney function stays stable. If eGFR drops below 45, the dose must be cut again. Below 30? It’s usually stopped entirely.

Same with gabapentin. A typical starting dose is 300 mg at night. For seniors, it’s often 100-150 mg. Go too fast, and you risk falls, confusion, or dizziness - side effects that are far more dangerous in older adults. A fall isn’t just a bruise. It can mean a hip fracture, surgery, long-term care, or worse.

This rule applies to almost everything: blood pressure pills, sleep aids, pain relievers, even antidepressants. The goal isn’t to eliminate the drug - it’s to find the lowest dose that still works. Sometimes, that’s half the dose. Sometimes, it’s a completely different drug.

How Doctors Measure What Your Body Can Handle

Doctors don’t guess. They use tools. The most common one is the Cockcroft-Gault equation to estimate kidney function:CrCl = [(140 - age) × weight(kg)] / [72 × serum creatinine(mg/dL)] × 0.85 (for women)

If your creatinine clearance (CrCl) falls below 50 mL/min, most drugs cleared by the kidneys need a dose reduction. For example, if you’re on ciprofloxacin and your CrCl is 40, your dose might drop from 500 mg twice daily to 250 mg twice daily.

For drugs processed by the liver - like opioids, antipsychotics, or some seizure meds - doctors use the Child-Pugh score. It checks liver enzymes, bilirubin, albumin, and signs of fluid buildup. A score of 7-9 means moderate liver trouble. That usually means cutting the dose by half. A score of 10-15? That’s severe. Many drugs are avoided entirely.

And it’s not just lab numbers. Functional tests matter too. If you can’t stand up from a chair without using your hands, or if it takes you more than 12 seconds to walk 3 meters and turn around (the Timed Up and Go test), you’re likely frail. Frailty means your body has less reserve. Even a normal dose can push you over the edge.

The Most Dangerous Drugs for Seniors

The 2023 Beers Criteria® from the American Geriatrics Society lists 30 classes of drugs that are risky for older adults. These aren’t obscure meds - they’re common ones.- Benzodiazepines (like lorazepam, diazepam): Increase fall risk by 50%. Avoid for sleep or anxiety. Safer alternatives exist.

- NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen): Raise risk of stomach bleeding by 300%. Even occasional use can be dangerous. Acetaminophen is usually safer - but watch your liver.

- Anticholinergics (diphenhydramine, oxybutynin): Double dementia risk with long-term use. Found in many sleep aids, allergy pills, and bladder meds.

- Antipsychotics (quetiapine, risperidone): Used for behavior issues in dementia - but increase stroke and death risk. Only for severe cases, short-term.

- Warfarin: Requires 20-30% lower doses in seniors. Needs frequent blood tests. Newer blood thinners like apixaban are often safer.

These drugs aren’t banned. But they should be used only when absolutely necessary - and at the lowest possible dose. Many seniors are on them because no one ever stopped them.

Why Polypharmacy Is a Silent Crisis

More than half of older adults take five or more prescription drugs. That’s called polypharmacy. It’s not always bad - if you have heart disease, diabetes, and arthritis, you need multiple meds. But the more drugs you take, the higher the chance of bad interactions and side effects.Take a 78-year-old woman on lisinopril (blood pressure), metformin (diabetes), atorvastatin (cholesterol), oxycodone (pain), and sertraline (depression). That’s five drugs. Each one affects her kidneys, liver, and brain differently. Now add an over-the-counter sleep aid with diphenhydramine - an anticholinergic. Suddenly, she’s confused in the morning, constipated, and her blood pressure drops too low.

That’s why medication reviews are critical. The Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI) is a 10-point checklist doctors can use. A score over 18 means the regimen is inappropriate. It flags things like wrong dose, wrong drug, or no clear reason for the med.

Pharmacists can cut medication errors by 67% just by reviewing these lists. That’s why programs like the University of North Carolina’s Pharm400 - where pharmacists meet weekly with seniors, organize pills in blister packs, and adjust doses - reduced hospitalizations by 22%.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t need to wait for your doctor to bring this up. Be proactive.- Do a brown bag review. Take every pill, vitamin, and supplement you take - in the original bottles - to your next appointment. Don’t rely on memory.

- Ask: “Is this still necessary?” Especially if you’re on something for a short-term issue that never went away.

- Ask about kidney and liver function. Request your eGFR and liver enzyme numbers. Know your numbers.

- Don’t take OTC meds without asking. Many seniors don’t realize that Advil or Benadryl are drugs too.

- Involve a family member. Studies show that when a caregiver helps manage meds, adherence improves by 37%.

Many seniors are afraid to question their doctor. But your health is your business. If your doctor won’t discuss dose changes, find one who will. There are over 70% more hospitals now with geriatric pharmacists on staff than there were in 2015. You can get expert help.

The Future Is Personalized Dosing

The future isn’t just about age. It’s about function. Researchers are moving away from “65+” as a cutoff. Instead, they’re looking at gait speed, grip strength, cognitive tests, and real-world function to guide dosing.AI tools like MedAware are already helping pharmacists predict dangerous interactions and suggest adjustments. In a 2023 Johns Hopkins pilot, these tools cut dosing errors by 47%. By 2030, personalized pharmacokinetic dosing - where your blood levels, organ function, and genetics guide your dose - will likely be standard for high-risk drugs.

But right now, the biggest barrier isn’t technology. It’s awareness. Over 65% of U.S. physicians say they didn’t get enough training in geriatric pharmacology. That’s why you need to be your own advocate.

You’re not too old to ask questions. You’re not too old to change your meds. You’re not too old to live better - and safer - with the right dose.

Why can’t I just take the same dose I always have?

Your body changes as you age. Your kidneys and liver process drugs slower, your body fat increases, and your muscle mass decreases. These changes mean drugs stay in your system longer and can build up to toxic levels. A dose that was safe at 50 can become dangerous at 75.

What is the Beers Criteria and why does it matter?

The Beers Criteria is a list of medications that are potentially inappropriate for older adults because they carry high risks of side effects like falls, confusion, kidney damage, or bleeding. Updated every two years by the American Geriatrics Society, it helps doctors avoid drugs that do more harm than good in seniors - even if they were prescribed years ago.

How do I know if my kidney function is low?

Your doctor can check your kidney function with a simple blood test that measures creatinine and calculates your eGFR (estimated glomerular filtration rate). If your eGFR is below 60 for three months or more, your kidneys are not working well. Many seniors have eGFR below 60 without knowing it - that’s why testing is essential.

Can I stop my medication if I feel fine?

No. Stopping a medication suddenly can be dangerous - especially for blood pressure, heart, or seizure drugs. But if you feel fine, it’s a good sign to ask your doctor if you still need it. Some meds are prescribed for short-term use but kept on automatically. A medication review can help determine what’s still necessary.

Are over-the-counter drugs safe for seniors?

Many are not. Common OTC drugs like diphenhydramine (Benadryl), ibuprofen (Advil), and naproxen (Aleve) carry high risks for older adults. Diphenhydramine increases dementia risk and causes dizziness. NSAIDs can cause stomach bleeding and kidney damage. Always check with your pharmacist or doctor before taking any OTC medicine.

What should I bring to my medication review?

Bring all your medications - prescription, over-the-counter, vitamins, and supplements - in their original bottles. Include any herbal remedies or CBD products. This is called a “brown bag review.” It helps your provider see exactly what you’re taking and catch duplicates, interactions, or unnecessary drugs.

If you’re managing multiple medications, don’t wait for a crisis. Schedule a full medication review with your doctor or pharmacist. Ask about your kidney and liver numbers. Question every pill on your list. Your body isn’t the same as it was 20 years ago - your meds shouldn’t be either.

Saket Modi

December 3, 2025 AT 13:24Girish Padia

December 4, 2025 AT 00:12John Biesecker

December 5, 2025 AT 08:26Genesis Rubi

December 6, 2025 AT 09:16Kristen Yates

December 7, 2025 AT 09:53Saurabh Tiwari

December 7, 2025 AT 12:45Michael Campbell

December 8, 2025 AT 02:50Victoria Graci

December 9, 2025 AT 19:36Saravanan Sathyanandha

December 11, 2025 AT 08:29alaa ismail

December 13, 2025 AT 01:43Carolyn Woodard

December 13, 2025 AT 17:07Allan maniero

December 14, 2025 AT 01:24Zoe Bray

December 15, 2025 AT 09:16Sandi Allen

December 17, 2025 AT 08:49