Bipolar Antidepressant Risk Calculator

How Your Risk Is Calculated

This calculator uses data from the article to estimate your risk of experiencing a mood switch (manic or hypomanic episode) when taking antidepressants based on your individual factors.

Why Antidepressants Can Make Bipolar Disorder Worse

For years, doctors treated bipolar depression the same way they treated regular depression: with antidepressants. It seemed logical. If a drug lifts mood in someone with unipolar depression, why not use it for someone with bipolar depression? But the reality is far more dangerous. In bipolar disorder, antidepressants don’t just help-they can trigger mania, rapid cycling, or even suicidal thoughts. This isn’t a rare side effect. It’s a well-documented, predictable risk.

Studies show that about 12% of people with bipolar disorder who take antidepressants experience a switch into mania or hypomania. In some groups-like those with a history of prior switches or mixed episodes-that number jumps to 31%. That’s not a small chance. It’s a serious gamble. And the stakes are high: hospitalizations, job loss, broken relationships, and sometimes, suicide.

Which Antidepressants Are Riskiest?

Not all antidepressants are created equal when it comes to bipolar disorder. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) like amitriptyline carry the highest risk, with switch rates between 15% and 25%. These older drugs affect multiple brain chemicals at once, making mood swings more likely.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) like sertraline or fluoxetine are considered safer-but only relatively. Their switch risk is around 8% to 10%. Still, even that small percentage means one in ten people could spiral into mania after starting one. Bupropion (Wellbutrin) is often preferred because it doesn’t strongly affect serotonin, and studies suggest it has a lower risk of triggering mania than SSRIs. But it’s not risk-free.

SNRIs like venlafaxine? Avoid them. They’re more likely to cause rapid cycling-where mood swings happen faster than every few days. And monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)? Rarely used today, but when they are, they come with even higher instability risks.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone with bipolar disorder reacts the same way to antidepressants. Some people can take them safely for months without issue. Others go from depressed to manic after one pill. Why? Several key factors determine your risk:

- Bipolar I vs. Bipolar II: People with Bipolar I (who’ve had full manic episodes) are far more likely to switch than those with Bipolar II (who only have hypomania).

- History of antidepressant-induced mania: If you’ve had a manic episode after taking an antidepressant before, your chance of it happening again is 3.2 times higher.

- Rapid cycling: If you’ve had four or more mood episodes in a year, antidepressants are likely to make it worse. About 18-25% of bipolar patients are rapid cyclers.

- Mixed features: If your depression comes with symptoms like irritability, racing thoughts, or impulsivity, you’re in a high-risk group. About 20% of bipolar depressions have mixed features-and antidepressants can turn them into full-blown episodes.

What Are the Alternatives?

The FDA has approved four medications specifically for bipolar depression-and none of them are traditional antidepressants. These are your safer options:

- Quetiapine (Seroquel): Works well for depression, with only 5% or less risk of switching.

- Lurasidone (Latuda): One of the most effective, with a 2.5% switch rate and strong evidence for improving daily function.

- Cariprazine (Vraylar): Shows good results in depression, with a 4.5% risk of mania.

- Olanzapine-fluoxetine combo (Symbyax): A mix of an antipsychotic and an SSRI, but even here, the antidepressant component is tightly controlled.

These drugs don’t just treat depression-they stabilize your mood long-term. That’s the difference. Antidepressants treat a symptom. These treat the illness.

The Efficacy Myth: Do Antidepressants Even Work?

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: antidepressants aren’t very effective for bipolar depression. The number needed to treat (NNT)-meaning how many people you have to treat to get one person to respond-is 29.4. That means you’d need to give antidepressants to nearly 30 people to help one of them feel better.

Compare that to unipolar depression, where the NNT is just 6 to 8. Or to quetiapine, which helps about half of patients with a much lower risk. In bipolar disorder, the benefit is tiny. The risk? Huge.

Even the STEP-BD study, one of the largest ever done on bipolar depression, found that adding an antidepressant to a mood stabilizer helped only 36.8% of patients reach remission. The group on mood stabilizers alone? 35.9%. No meaningful difference. But the antidepressant group had more mood switches.

Why Do Doctors Still Prescribe Them?

If the risks are so high and the benefits so low, why are antidepressants still so common? The answer is messy.

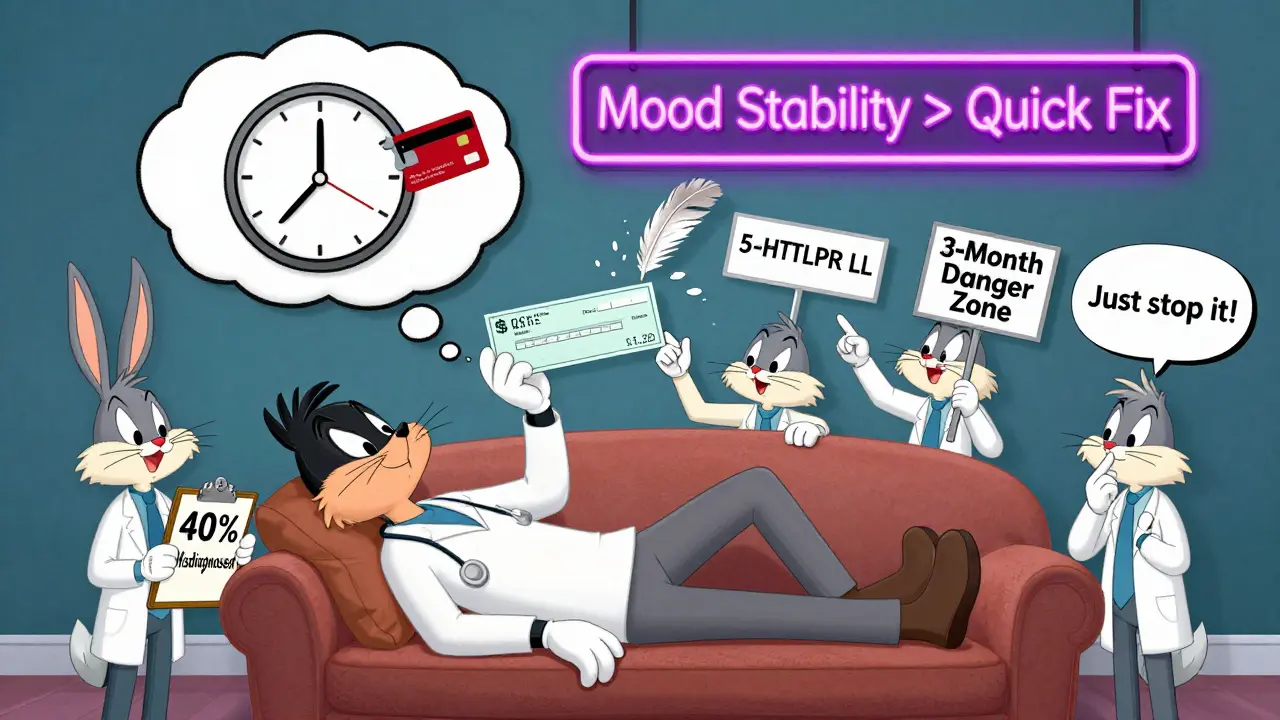

First, many doctors aren’t specialists. A general practitioner or even a community psychiatrist may not have the training to recognize bipolar disorder correctly. Up to 40% of people with bipolar disorder are initially misdiagnosed with unipolar depression. Once they’re on an antidepressant, it’s hard to stop-even when signs of mania appear.

Second, patients want relief. Fast. Antidepressants can start working in 2-4 weeks. Mood stabilizers like lithium or lamotrigine? They take 4-6 weeks or longer. In a crisis, doctors feel pressured to act quickly-even if it’s not the safest move.

Third, the pharmaceutical industry still pushes antidepressants. About 50-80% of bipolar patients in the U.S. are prescribed them, generating over $1.2 billion a year in off-label sales. Academic centers follow guidelines more closely-only 38% prescribe them. Community clinics? Up to 80%.

When Might Antidepressants Be Okay?

There are rare cases where antidepressants might be considered. But only under strict conditions:

- You have severe, treatment-resistant depression after trying at least two FDA-approved bipolar meds with no success.

- You have no history of mania triggered by antidepressants.

- You have no mixed features or rapid cycling.

- You’re taking a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic at the same time-never alone.

- You’re monitored weekly for the first month for any signs of energy, sleep loss, irritability, or impulsivity.

- You plan to stop the antidepressant within 8-12 weeks, even if you feel better.

Even then, many experts-like Dr. Nassir Ghaemi at Tufts-use antidepressants in fewer than 20% of their bipolar patients. They’re not a tool. They’re a last-resort.

What Happens If You’re Already on One?

If you’re currently taking an antidepressant for bipolar disorder, don’t stop cold turkey. That can cause withdrawal or worsen depression. Talk to your doctor about a plan.

Start by asking:

- Why was this prescribed?

- Have I had any signs of mania or hypomania since starting it?

- Have I been on it longer than 12 weeks?

- Am I on a mood stabilizer too?

If you’ve been on it for more than 3 months, you’re likely in the danger zone. Studies show long-term use (>24 weeks) increases your risk of more frequent episodes by 37%. The goal isn’t to stay on it forever-it’s to get off it as soon as possible.

What to Watch For: Early Signs of a Switch

Mania doesn’t always mean yelling or grandiosity. Often, it starts quietly:

- Needing less sleep but feeling energized

- Starting too many projects and not finishing any

- Feeling unusually irritable or impatient

- Spending money recklessly

- Talking faster than usual or jumping between ideas

- Feeling overly confident or invincible

If you notice even one of these after starting an antidepressant, contact your doctor immediately. Don’t wait. Don’t assume it’s just "feeling good." In bipolar disorder, feeling too good is often the first step toward a crash.

The Future: Better Treatments on the Horizon

The field is moving away from antidepressants. New drugs are being developed that treat depression without triggering mania. Esketamine (Spravato), a nasal spray derived from ketamine, has shown a 52% response rate in bipolar depression with only a 3.1% switch risk. That’s better than any traditional antidepressant.

Researchers are also looking at genetics. A specific variation in the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR) may predict who’s more likely to switch. If you have the LL genotype, your risk could be 3.2 times higher. In the future, a simple genetic test might tell you whether an antidepressant is safe for you.

But until those tools are widely available, the safest path remains clear: avoid antidepressants unless absolutely necessary-and even then, use them briefly, with full monitoring, and never alone.

Final Thought: It’s Not About Willpower

If you’ve been told to "just try an antidepressant" for your bipolar depression, you’re being given bad advice. This isn’t about being weak or not trying hard enough. It’s about biology. Bipolar disorder isn’t just depression with mood swings. It’s a distinct illness with different rules. Treating it like unipolar depression doesn’t help-it harms.

The goal isn’t to feel better for a few weeks. It’s to stay stable for years. That means choosing treatments that protect your mood long-term-not ones that risk destroying it.

Jasmine Bryant

January 22, 2026 AT 11:24Liberty C

January 22, 2026 AT 13:55Brenda King

January 22, 2026 AT 20:00Rob Sims

January 24, 2026 AT 18:08Chiraghuddin Qureshi

January 26, 2026 AT 12:13Kenji Gaerlan

January 27, 2026 AT 10:22Oren Prettyman

January 27, 2026 AT 19:00Malik Ronquillo

January 27, 2026 AT 19:40Daphne Mallari - Tolentino

January 28, 2026 AT 15:21Neil Ellis

January 30, 2026 AT 00:01Alec Amiri

January 30, 2026 AT 11:10