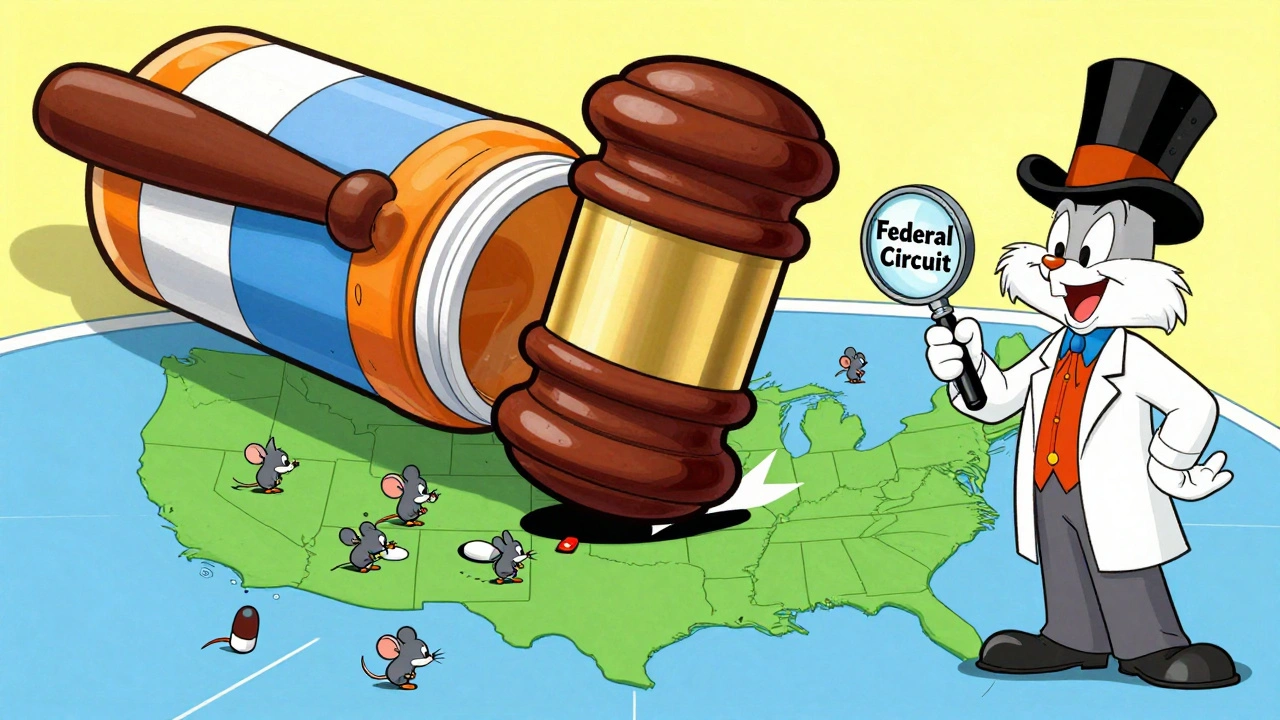

The Federal Circuit Court doesn’t just hear patent cases-it decides how generic drugs reach the market, how long brand-name drugs keep their monopoly, and whether a new dosage form can be patented at all. This single court controls the entire U.S. pharmaceutical patent system. If you’re developing a generic drug, challenging a patent, or trying to protect a new dosing regimen, your fate hinges on rulings from this court in Washington, D.C.

Why the Federal Circuit Holds All the Power

Unlike other federal appeals courts that handle a mix of criminal, civil, and immigration cases, the Federal Circuit has one job: patent law. Since 1982, Congress gave it exclusive authority over all patent appeals. That includes every single pharmaceutical patent case filed anywhere in the country. A lawsuit started in Delaware, Texas, or California? If it involves a patent, it ends up here. This isn’t just about convenience. It means every ruling on drug patents sets a nationwide precedent. A decision in one case becomes the rule for every other case. That’s why pharmaceutical companies watch every Federal Circuit opinion like stock market news.ANDA Filings Create Nationwide Jurisdiction

One of the biggest shifts came in 2016, in a case involving Mylan. The court ruled that filing an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with the FDA isn’t just paperwork-it’s a legal declaration that you intend to sell your drug across the entire United States. That means a generic company can be sued in any state where the patent holder chooses to file, even if the company has no offices or employees there. Before this, companies often fought over where to file lawsuits. Now, plaintiffs routinely file in Delaware, a favorite because of its experienced judges and predictable rulings. Between 2017 and 2023, 68% of ANDA lawsuits were filed there, up from just 42% in the previous decade. This has pushed legal costs up dramatically. What used to cost $5.2 million per case now averages $8.7 million. The court made it clear: if your ANDA says you plan to sell your drug nationwide, then you’ve created legal ties to every state. The Samsung Bioepis case in 2024 extended this even further-biosimilars, not just generics, are subject to the same rule.The Orange Book Isn’t Just a List-It’s a Legal Weapon

The FDA’s Orange Book lists patents tied to brand-name drugs. It’s not a directory. It’s a gatekeeper. If a patent isn’t listed there, a generic company can launch without fear of infringement suits. In December 2024, the Federal Circuit ruled in Teva v. Amneal that only patents that actually claim the specific drug substance can be listed. If a patent describes a method of use but doesn’t claim the drug itself, it can’t stay on the list. This forced companies to clean up their Orange Book entries. Many patents were removed, opening the door for generics. Now, pharmaceutical companies spend weeks mapping each patent to the exact drug formulation. Legal teams do “patent-drug claim mapping” before even submitting an ANDA. According to a 2024 survey, this extra review adds 17 business days to the pre-filing process.

Patenting Dosing Regimens? Good Luck

One of the most controversial areas is dosing. Can you patent a new way to take a drug-like taking it once a day instead of three times? In the past, courts sometimes said yes. Not anymore. In April 2025, the court ruled in ImmunoGen v. a generic manufacturer that simply changing the dose of a known drug isn’t enough for a patent. The court said: “If the drug itself was already known to treat the disease, then the only question is whether the new dose was obvious.” That’s a huge shift. Before, companies would file dozens of secondary patents on dosing schedules to extend their market exclusivity. Now, they’re cutting back. Clarivate’s 2024 analysis found that filings for dosing patents dropped 37% after the ImmunoGen decision. Instead, companies are spending more on developing entirely new compounds-up 22% in R&D investment. The court’s message is clear: incremental changes won’t cut it. You need real innovation.Standing: Can You Even Sue?

Here’s the catch: you can’t just challenge a patent because you don’t like it. You need to show you’re actually planning to make a competing drug. In May 2025, the court ruled in Incyte v. Sun Pharma that vague intentions aren’t enough. You need concrete evidence-Phase I clinical trial data, manufacturing plans, supply chain contracts. This has created a new hurdle for generic companies. Many delay challenging patents until they’re ready to launch. But that means they risk losing the 30-month stay period, which delays generic entry. Some industry insiders say the court’s standing rules are now a barrier to competition. Judge Hughes, in his concurrence, openly questioned whether the current standard “stifles generic competition.” His comments have sparked a new bill in Congress-the Patent Quality Act of 2025-which aims to lower the standing bar for generic drugmakers.

How This Affects Real People

These rulings aren’t abstract legal points. They directly affect drug prices and access. When the court makes it harder to patent dosing regimens, more generics enter the market faster. That lowers prices. When it makes jurisdiction easier for brand companies, litigation becomes more expensive and delays generic entry. That keeps prices high. The court’s decisions have also impacted biosimilars-copycat versions of biologic drugs like Humira or Enbrel. Since 2020, litigation in this space has jumped 300%. That’s because the Federal Circuit extended the same jurisdiction rules from ANDA cases to biosimilars. The result? More competition in high-cost drug categories. But also more legal risk for companies trying to enter.What’s Next?

The Federal Circuit isn’t slowing down. Its rulings continue to tighten the rules around patenting, jurisdiction, and standing. Analysts predict a 15-20% drop in “evergreening” strategies by 2027-where companies file multiple patents just to delay generics. But core compound patents? Those are still strong. The court has affirmed 82% of validity challenges on the original drug molecule. That means innovation in new chemical entities is still rewarded. For generic manufacturers, the path is clear: document everything. Show real development activity. Avoid weak dosing patents. And know that filing an ANDA isn’t just a step toward market entry-it’s a legal trigger that can pull you into court anywhere in the U.S. For brand companies, the message is equally clear: make sure your patents actually claim the drug. Don’t rely on secondary patents. And be ready for the courts to demand real proof before letting you block competition. The Federal Circuit doesn’t just interpret patent law. It shapes the entire pharmaceutical ecosystem. Every decision ripples through labs, manufacturing plants, pharmacies, and patients’ medicine cabinets.Why does the Federal Circuit have exclusive control over pharmaceutical patent cases?

The U.S. Congress created the Federal Circuit in 1982 through the Federal Courts Improvement Act to centralize patent appeals. Before that, different circuit courts made conflicting rulings on patent law, creating confusion for businesses. By giving one court exclusive jurisdiction over all patent cases-including pharmaceutical patents-the system became more predictable. Now, every patent appeal from any federal district court in the country goes to the Federal Circuit. This ensures uniform standards for patent validity, infringement, and jurisdiction across the entire U.S.

Can a generic drug company be sued in any state after filing an ANDA?

Yes. Since the 2016 Mylan ruling, the Federal Circuit has held that filing an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) with the FDA demonstrates intent to market the drug nationwide. That creates personal jurisdiction in any state where the patent holder files suit. This is why most brand-name companies now file lawsuits in Delaware-it has experienced judges and a history of favorable rulings for patent holders. Over 68% of ANDA cases between 2017 and 2023 were filed there, even if the generic company had no physical presence in the state.

What is the Orange Book and why does it matter for generic drugs?

The Orange Book, officially titled “Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations,” is a list maintained by the FDA that links brand-name drugs to patents held by their manufacturers. For a generic company to launch, it must either wait until all listed patents expire or prove those patents are invalid or not infringed. In 2024, the Federal Circuit ruled that only patents that actually claim the specific drug substance can be listed. If a patent describes a use or method but doesn’t claim the drug itself, it must be removed. This forces companies to be precise in their patent filings and prevents them from blocking generics with weak or unrelated patents.

Can you patent a new dosage schedule for an existing drug?

It’s extremely difficult now. The Federal Circuit’s 2025 decision in ImmunoGen v. a generic manufacturer set a strict standard: if the drug itself was already known to treat a disease, changing the dose or schedule alone is not enough to be patentable. The court requires proof that the new dosing produces unexpected results-not just convenience or minor improvements. This has led pharmaceutical companies to reduce secondary patent filings for dosing regimens by 37% since April 2025, shifting focus instead to developing entirely new compounds.

Do I need clinical trial data to challenge a pharmaceutical patent?

Yes. After the May 2025 Incyte decision, the Federal Circuit requires companies challenging a patent to show concrete, immediate plans to develop a competing product. Vague intentions or market research aren’t enough. You need documented evidence-like Phase I clinical trial protocols, manufacturing agreements, or supply chain contracts. Without this, the court will dismiss your case for lack of standing. This rule was designed to prevent “patent trolling” but has made it harder for smaller generic companies to challenge patents before investing heavily in development.

John Filby

December 4, 2025 AT 03:43Man, I didn’t realize filing an ANDA was basically signing a legal contract to get sued anywhere. That’s wild. My cousin works at a generic pharma startup and they’re terrified of Delaware courts now. Guess we’re all just pawns in this patent chess game.

Elizabeth Crutchfield

December 4, 2025 AT 21:13orange book is such a mess lol. so many patents that dont even make sense but they still get listed. i hate how they use it to block generics. its not fair.

Ben Choy

December 6, 2025 AT 07:30It’s insane how much power one court has. I mean, imagine if the UK Supreme Court suddenly got exclusive control over all patent cases. It’d be chaos. But here, it’s just… normal? The Federal Circuit’s rulings basically dictate whether a $200k drug becomes a $5 generic. That’s not justice, that’s corporate roulette.

Emmanuel Peter

December 6, 2025 AT 12:23Let’s be real - this whole system is rigged. The ‘innovation’ these pharma giants brag about? Half of it is just rebranding the same damn pill with a new color and calling it ‘once-daily.’ They’re not inventing, they’re gaming the system. And the court? They’re just the enforcers for Big Pharma’s monopoly playbook. Wake up, people - your insulin isn’t expensive because of R&D. It’s expensive because they can be.

Ashley Elliott

December 8, 2025 AT 08:38I’ve been reading up on this for my bioethics class, and honestly… it’s terrifying how much this affects real people. I have a friend with lupus who can’t afford her biologic - and it’s not because the science is hard. It’s because lawsuits delay generics for years. The court’s rulings aren’t abstract - they’re life-or-death. We need to fix this.

Chad Handy

December 10, 2025 AT 08:02You know what’s really messed up? The fact that the Federal Circuit doesn’t even have a jury. Just a bunch of judges who’ve spent their entire careers in patent law - and most of them used to work for Big Pharma firms before they got appointed. So now they’re deciding whether a generic company can sell a drug that could save thousands of lives… and they’re basically judging their former clients. It’s like the foxes are running the henhouse and writing the rules for how many chickens each fox gets to eat. And don’t even get me started on how they’ve twisted ‘standing’ into a weapon. You need Phase I trial data to challenge a patent? That’s like saying you need to already be a chef before you can complain about a restaurant’s poisoned food. It’s not just biased - it’s actively hostile to competition.

Augusta Barlow

December 12, 2025 AT 02:36They say this is about ‘patent quality’ but let’s be honest - this is all part of the deep state’s plan to control drug prices. You think Congress doesn’t know what’s going on? They’re just letting the Federal Circuit do their dirty work so they can pretend they’re not the ones raising insulin prices. And now they’re pushing this ‘Patent Quality Act’? Please. It’s a distraction. Meanwhile, the same companies that lobbied for this system are now funding think tanks to spin it as ‘pro-innovation.’ It’s all smoke and mirrors. Wake up. This isn’t law - it’s corporate propaganda dressed up in robes.

Joe Lam

December 13, 2025 AT 22:08Wow, you all sound like you just read the first page of a 500-page law review article. The Federal Circuit didn’t ‘create’ this system - it was designed by Congress to fix decades of circuit splits that made patent law a national joke. The fact that you think ‘Delaware is rigged’ shows you don’t understand jurisdictional efficiency. Also, ‘evergreening’? That’s a lazy term used by people who don’t understand incremental innovation. A new dosing regimen isn’t ‘just rebranding’ - it’s clinical science. And yes, you need standing. If anyone could sue over any patent, we’d have 10,000 frivolous cases a year. This isn’t a conspiracy. It’s a legal framework. Try reading the actual opinions before you rant.

Jenny Rogers

December 14, 2025 AT 02:20One must contemplate, with the gravitas befitting the solemnity of jurisprudential inquiry, the ethical implications of a judicial body vested with quasi-legislative authority over the very architecture of pharmaceutical access. The Federal Circuit, in its institutional hubris, has transmuted the statutory mandate of patent protection - originally conceived as an incentive for innovation - into a mechanism of monopolistic entrenchment. The Orange Book, once a mere administrative registry, has become a legal instrument of exclusionary practice, wherein the commodification of therapeutic knowledge is weaponized against the vulnerable. One cannot help but invoke Kantian ethics: if the maxim of patent law is to ‘promote progress,’ then its current application violates the categorical imperative by treating patients as mere means to corporate ends. The Incyte standing doctrine, in particular, represents a profound moral failure - a judicial abdication of its duty to ensure equitable access to essential medicines. One must ask: in a society that purports to value human dignity, how can a court demand clinical trial data before permitting a challenge to a life-sustaining drug’s monopoly? This is not jurisprudence. It is the apotheosis of neoliberal legalism.

George Graham

December 15, 2025 AT 04:03Reading this made me think of my dad. He’s on three different meds, all generics now, but back in 2018, one of them jumped from $40 to $400 overnight because the patent got extended on a silly dosing schedule. I didn’t understand it then. Now I do. This court’s decisions aren’t just legal - they’re personal. Thank you for writing this. It’s the first time I’ve seen the whole picture.