When it comes to switching from a brand-name drug to a generic, most people assume it’s a simple, safe swap. But for certain medications - those with a narrow therapeutic index - that assumption can be dangerous. These drugs have a tiny window between the dose that works and the dose that causes harm. A small change in how the drug is absorbed can lead to seizures, blood clots, or even death. That’s why 27 U.S. states have passed special rules blocking or restricting generic substitutions for these drugs - even though the FDA says they’re just as safe.

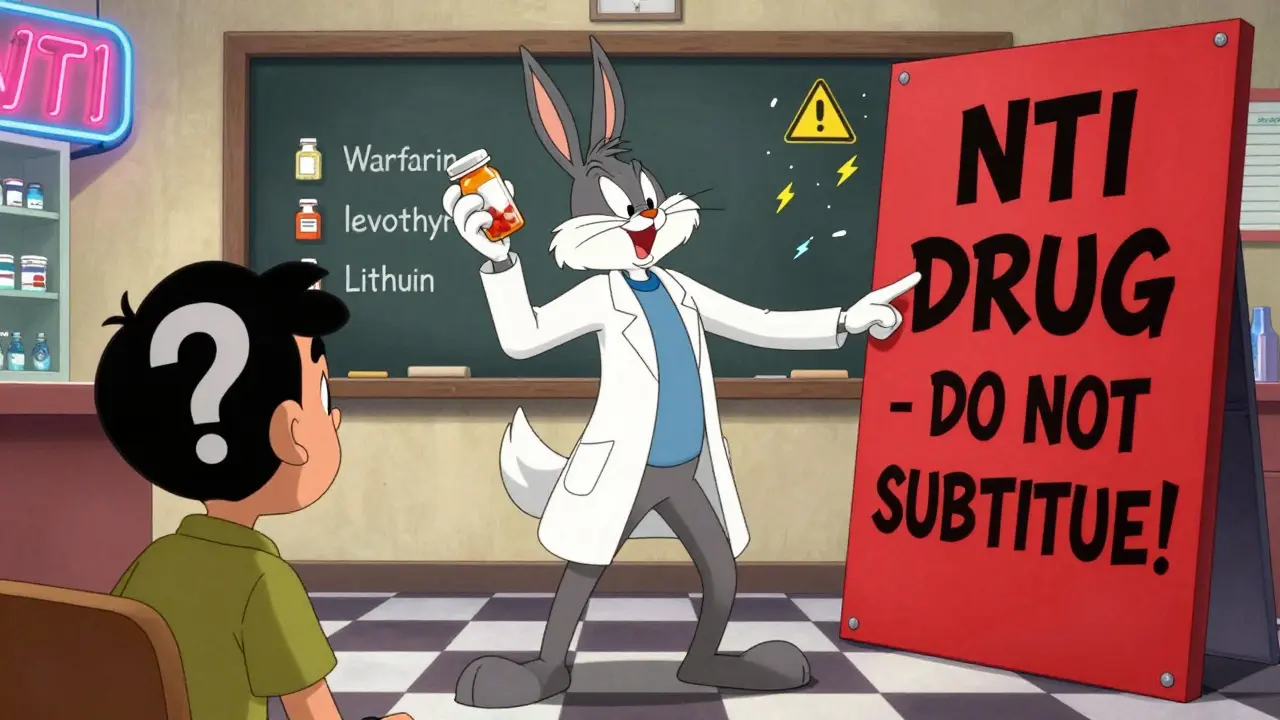

What Makes a Drug ‘Narrow Therapeutic Index’?

Narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs are medications where even a slight difference in blood levels can cause serious problems. Think of it like walking a tightrope: one step too far, and you fall. Drugs like warfarin (a blood thinner), levothyroxine (for thyroid conditions), lithium (for bipolar disorder), and certain anti-seizure medicines like phenytoin and carbamazepine fall into this category.

The FDA doesn’t officially label drugs as NTI in its Orange Book - the public list of approved generics. But state pharmacy boards don’t wait for federal approval. They act based on clinical experience, adverse event reports, and expert opinion. For example, Kentucky’s Board of Pharmacy explicitly lists digoxin, levothyroxine, lithium, and warfarin as drugs where substitution is prohibited unless the prescriber writes a note allowing it. In Pennsylvania, the same drugs are on a legally binding list that pharmacists must follow.

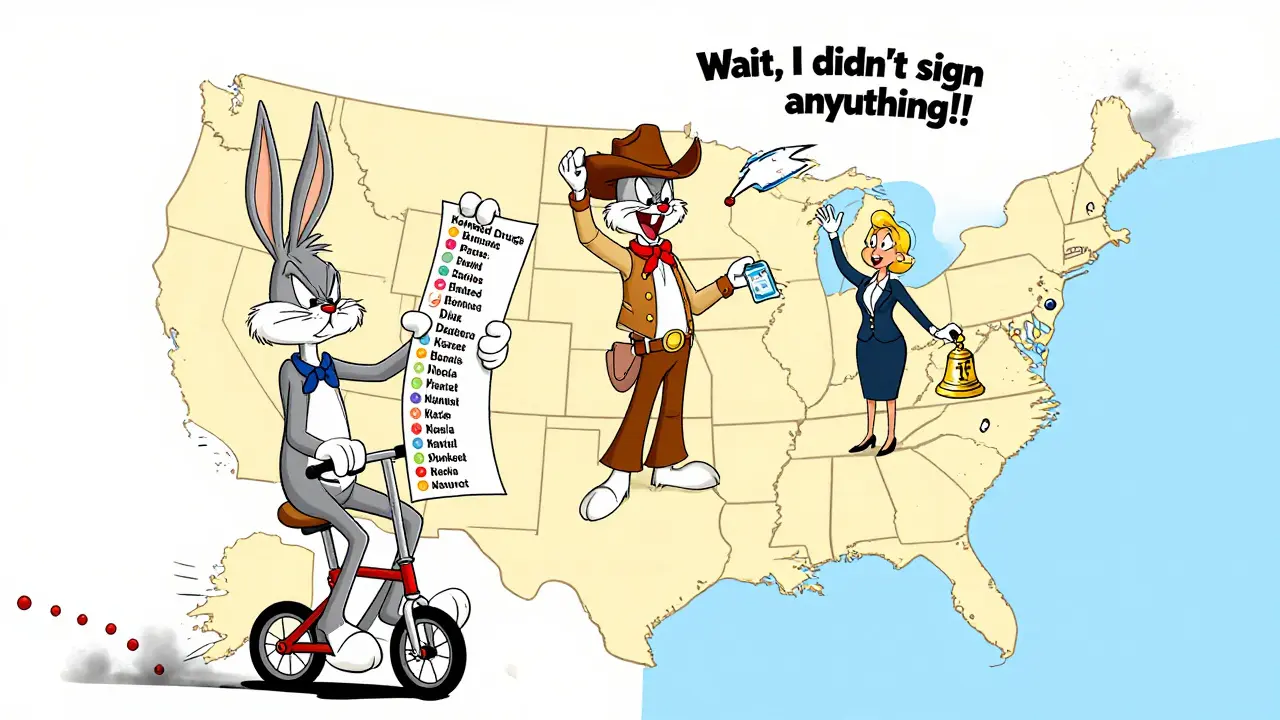

How States Differ: Three Types of Rules

Not all states handle NTI drugs the same way. There are three main models:

- Carve-out bans: 17 states outright prohibit substitution for certain NTI drugs. Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina are strict here - no swap unless the doctor says yes.

- Dual consent: 9 states require both the patient and the prescribing doctor to give written approval before a generic can be swapped in. North Carolina requires this for refill prescriptions of NTI drugs. Connecticut goes further: if you’re on an anti-seizure drug, the pharmacist must notify both you and your doctor within 72 hours of swapping, and either of you can stop it within 14 days.

- Notification-only: 11 states don’t ban substitution but require pharmacists to document and notify the prescriber when they switch an NTI drug. South Carolina, for example, recommends avoiding substitutions for lithium and Synthroid - but doesn’t make it mandatory.

The differences aren’t just legal - they’re practical. In states with carve-outs, pharmacists spend an average of 3.2 minutes per prescription checking if the drug is on the restricted list. In states without rules, it’s less than a minute. That adds up to nearly 9 extra hours a month for pharmacists in restrictive states.

Which States Have the Strictest Rules?

Some states are far more cautious than others:

- Kentucky: Has one of the most detailed NTI lists in the country. Substitution is banned for 27 specific drug products, including all strengths of levothyroxine and warfarin. Pharmacists must document prescriber authorization in the patient’s record.

- North Carolina: Requires signed consent from both patient and prescriber for any NTI drug substitution. Forms must be kept for three years.

- Connecticut: Focuses on anti-epileptic drugs. Any substitution triggers mandatory notification and a 14-day window for objections.

On the other end, states like California, Texas, and Virginia follow federal guidelines and allow substitution without extra steps. In Virginia, chain pharmacies report patient complaints about NTI substitutions are under 0.5% - suggesting that, for many, the swap works fine.

Why the Conflict Between States and the FDA?

The FDA insists that all approved generics - including those for NTI drugs - meet the same bioequivalence standards as brand-name versions. They say there’s no proven clinical difference in outcomes. But state pharmacy boards point to real-world data: patients on warfarin who switch generics sometimes see dangerous spikes or drops in their INR levels. A 2020 study in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes found no significant difference in INR stability between brand and generic warfarin in over 12,000 Medicare patients. But other studies, including one in JAMA Internal Medicine, show states with substitution bans had 28.7% fewer NTI-related adverse events.

Dr. Aaron Kesselheim from Harvard Medical School puts it plainly: “For drugs like warfarin, where a 10% difference in absorption can mean the difference between a clot and a stroke, the stakes are too high to ignore.” Meanwhile, the Generic Pharmaceutical Association argues that many drugs on state NTI lists - like certain antidepressants or statins - don’t even have strong evidence of a narrow therapeutic index. They say these rules are outdated and drive up costs.

Impact on Patients and Costs

These laws aren’t just about safety - they’re about money. NTI drugs account for $28.7 billion in annual prescriptions. In states with strict substitution rules, generic use for these drugs is 12.4% lower than in states without restrictions. That means patients pay more out of pocket, insurers pay more, and Medicaid spends more.

Some patients benefit. The Epilepsy Foundation says Connecticut’s rules led to a 19.2% drop in seizure-related ER visits after implementation. But others feel trapped. A pharmacist in Kentucky told a forum that checking the NTI list adds 5 to 7 minutes per prescription - time that could be spent counseling patients. And if a patient moves from Kentucky to Texas, they might suddenly get a generic they’ve never taken before - with no warning.

What’s Changing in 2025?

There’s movement toward consistency. California passed a law in 2022 requiring state NTI lists to be based on systematic clinical reviews, not tradition. New York is considering a bill that would define NTI drugs by a strict ratio of toxic to effective dose - a more scientific approach.

The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy is working on a model framework to help states align their rules. And the FDA released draft guidance in 2023 that could become the new standard for determining which drugs truly have a narrow therapeutic index.

But change is slow. States have historically claimed the right to protect public health under their police powers. And for many pharmacists and doctors, the fear of a patient having a bad reaction is too real to ignore.

What Should You Do If You’re on an NTI Drug?

If you take warfarin, levothyroxine, lithium, or an anti-seizure medication:

- Ask your pharmacist: “Is this a state-restricted NTI drug?”

- Check your prescription label - if it says “Dispense as Written” or “Do Not Substitute,” that’s your state’s rule in action.

- If you’re switched to a generic without your knowledge, ask why. You have the right to refuse.

- Keep a list of all your NTI medications and which brand or generic you’re on. Don’t assume the pharmacy will remember.

- If you move to a new state, ask your doctor to reconfirm your medication - rules change at the border.

The bottom line: For NTI drugs, the difference between brand and generic isn’t just about price. It’s about control, safety, and trust. Whether you’re in Kentucky or Kansas, know your rights - and don’t let a pharmacy swap your medication without you knowing.

Are generic NTI drugs really the same as brand-name ones?

The FDA says yes - all approved generics must meet the same bioequivalence standards. But for NTI drugs, even tiny differences in absorption can matter. Some patients report changes in how they feel after switching, and clinical studies show mixed results. That’s why states like Kentucky and North Carolina require extra steps - not because generics are unsafe, but because the margin for error is so small.

Can I ask my doctor to write ‘Do Not Substitute’ on my prescription?

Yes, absolutely. You have the right to request that your doctor mark your prescription as “Dispense as Written” or “Do Not Substitute.” This overrides state substitution laws and ensures you get the exact medication your doctor prescribed. It’s especially important if you’ve had issues with generic switches in the past.

Which states allow generic substitution for NTI drugs without restrictions?

As of 2025, states like California, Texas, Virginia, Georgia, and Arizona follow federal guidelines and allow substitution for NTI drugs without extra consent or documentation. Pharmacists in these states can swap generics as long as the drug is listed as therapeutically equivalent in the FDA’s Orange Book.

Why does Kentucky have such a long list of restricted NTI drugs?

Kentucky’s list was built over decades based on clinical reports and pharmacist concerns, not formal FDA designations. The state’s Board of Pharmacy added drugs like digoxin and lithium after observing adverse events linked to generic switches. While some experts argue the list includes drugs without strong evidence of narrow therapeutic index, Kentucky maintains that the precaution is necessary to prevent harm.

What happens if a pharmacist substitutes an NTI drug without consent in a restricted state?

In states with strict laws like North Carolina or Kentucky, unauthorized substitution is a violation of pharmacy law. The pharmacist can face fines, disciplinary action from the state board, or even loss of license. Patients are encouraged to report such incidents to their state board of pharmacy. Most pharmacy software now flags NTI drugs automatically, but human error still happens.

Gary Hartung

December 25, 2025 AT 18:48Oh, PLEASE. Another one of these ‘dangerous generics’ scare tactics. The FDA has reviewed over 10,000 studies-10,000-and still says: no meaningful difference. But oh no, Kentucky’s pharmacists are ‘protecting’ us from the Great Generic Conspiracy. I swear, if I had a dollar for every time a state legislature passed a law based on anecdotal horror stories instead of data, I’d own a private island. And yet, here we are-wasting 9 extra hours a month on paperwork because someone’s cousin’s dog got a different pill shape and cried. It’s not safety-it’s theater.

Ben Harris

December 26, 2025 AT 22:34Look I get it people are scared but you know what’s scarier the system that lets a pharmacist decide what medicine you get without even telling you. I had a friend on lithium who got switched and ended up in the ER because the generic made him feel like his brain was melting. No warning no consent just bam here’s your new pill. And now they want to cut corners. I don’t care what the FDA says if your brain feels like it’s being rewired by a toddler with a hammer then you have a problem. Stop pretending this is about money it’s about control.

Mussin Machhour

December 27, 2025 AT 23:14As a pharmacist in Ohio I see this every day. We’re not trying to be the bad guys. We just want to keep people safe. In states with no rules I’ve had patients come back saying ‘I feel weird’ after a switch and half the time they didn’t even realize it happened. The extra minute we spend checking the NTI list? That’s the minute that might prevent a seizure or a stroke. It’s not about bureaucracy-it’s about being human. Let’s not pretend this is just a cost issue. Real people are on the line here.

Justin James

December 28, 2025 AT 13:11Did you know the FDA is owned by Big Pharma? They’ve been quietly pushing this ‘generics are equal’ narrative since the 90s to kill off small manufacturers and consolidate profits. The real NTI drugs aren’t even on the list-like the ones that affect your gut microbiome or your epigenetic markers. The FDA doesn’t test for that. They test for blood levels. But what if the generic alters your serotonin transporters differently? What if it’s not the dose-it’s the filler? Corn starch vs. lactose? You think that doesn’t matter? They’re silencing the real science. And Kentucky? They’re the only ones not asleep at the wheel. Wake up people. This isn’t about drugs. It’s about your soul being chemically manipulated by invisible hand.

Winni Victor

December 30, 2025 AT 00:56Ugh. So let me get this straight-we’re spending billions so people can have the *exact same* drug but with a different logo? And somehow this is a crisis? I’m just sitting here wondering why we don’t just give everyone brand name and be done with it. Like, if you’re going to make a whole legal system around a pill, maybe the pill isn’t the problem. Maybe the problem is that we treat medicine like a vending machine. Also I hate that I have to Google ‘is this NTI’ every time I refill my meds. Can we just… stop?

Lindsay Hensel

December 30, 2025 AT 11:26Thank you for this comprehensive and deeply necessary overview. The disparity between state regulations and federal guidelines is not merely a legal inconsistency-it is a profound public health fragmentation. Patients deserve clarity, continuity, and above all, dignity in their care. The emotional and psychological burden of unpredictable medication changes cannot be quantified in dollars alone. I urge all stakeholders to prioritize patient autonomy and clinical evidence over political expediency.

Christopher King

December 31, 2025 AT 11:23Let me tell you what’s really going on. The pharmaceutical-industrial complex doesn’t want you to know that generics are just repackaged poison with cheaper dyes. The FDA’s ‘bioequivalence’ standards? A joke. They test on healthy volunteers, not people with liver disease, or PTSD, or autoimmune disorders. And the states that allow swaps? They’re all on the payroll of the big pharma lobbyists. You think Kentucky’s list is arbitrary? Look at who funded the last FDA advisory panel. You think your ‘cheap’ generic isn’t made in a factory that also produces rat poison? Wake up. They’re testing on you. And they’ve been doing it for decades. The real danger isn’t the pill-it’s the silence.

Bailey Adkison

January 1, 2026 AT 07:52States have no authority to override FDA approval. The Constitution is clear. The FDA’s Orange Book is the national standard. Any state law that restricts substitution based on subjective fears is ultra vires. The fact that pharmacists are being forced to act as gatekeepers instead of professionals is a violation of both medical ethics and federal supremacy. If you don’t trust the FDA then don’t use prescription drugs. But don’t impose your paranoia on the rest of us. This is not public health. This is legal chaos.

Michael Dillon

January 2, 2026 AT 15:43So I’m in Texas and my pharmacist swaps my levothyroxine every time. No big deal. I’ve been on the same dose for 8 years. My TSH is perfect. My hair stopped falling out. My energy’s back. I’ve tried three different generics. All fine. I’ve never had a problem. Meanwhile my cousin in Kentucky has to get her doctor to sign a form every time. And she’s mad about it. Why should she pay more and jump through hoops just because some state thinks it’s being extra safe? We’re not talking about insulin here. We’re talking about a pill that’s been used by millions. If it worked for me and 10 million others, maybe the fear is just… outdated.

Jason Jasper

January 3, 2026 AT 15:40I’ve been on warfarin for 12 years. I’ve used brand and generic. I’ve had my INR checked religiously. No difference. But I still ask my pharmacist to confirm the brand every time. Just because. I don’t need a law to make me cautious. I just need to know what’s in my body. I don’t care what the state says. I care about my numbers. And if my pharmacist doesn’t know that, I’ll find one who does.

Katherine Blumhardt

January 5, 2026 AT 01:33OMG I JUST GOT SWITCHED TO A GENERIC AND I FELT LIKE I WAS DROWNING IN MY OWN SKIN 😭 I THOUGHT I WAS HAVING A PANIC ATTACK BUT IT WAS THE PILLLLLLLS!! I CALLED MY DOCTOR AND HE SAID IT WAS ‘ALL IN MY HEAD’ BUT I KNOW WHAT I FELT!! I WANT MY BRAND BACK AND I WANT A REFUND AND ALSO A THERAPIST AND MAYBE A PET UNICORN 🦄

sagar patel

January 5, 2026 AT 05:51India allows generic substitution without restriction. Millions use it daily. No epidemic. No crisis. Only cost savings and access. Why does America treat every pill like a nuclear device? The FDA standard is scientific. The state laws are emotional. The result? Inequality. The rich get brand. The poor get bureaucracy. This is not healthcare. This is class warfare disguised as safety.

Linda B.

January 6, 2026 AT 18:32Of course the FDA says generics are fine. They’re funded by the same corporations that profit from brand-name drugs. The real question isn’t whether the pills are bioequivalent-it’s whether the regulators are compromised. And if you think Kentucky’s list is too long, you haven’t read the full list of drugs that were pulled from the market after being ‘approved’ by the FDA. This isn’t about NTI. It’s about control. They don’t want you to know how little they actually know.